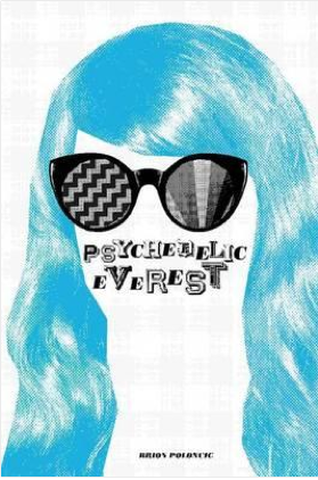

Psychedelic Everest

by Brian Poloncic

Auto-Interview

Q: I’ve read you are schizophrenic? What is that like?

A: Some days I choose not to wear my heart on my sleeve as much as others. I embrace it for Marketing sometimes, I’m not proud of that. Today is one of those days, but It’s true, I was Diagnosed with the “S” word when I turned 21. It’s a bitch sometimes., that’s what it’s like. Yeah, it’s hard but in some ways it saved my life…

Q: How is that?

A: It gives me time to write and draw, a lot of free-time really.

Q: You were once called the Daniel Johnston of the literary world. How does that work?

A: I might be, I don’t know. I am not bothered by the outsider artist thing though,

I’m broke you see, I’ll ride it as long as I can, but I think I’ll probably out grow that.

Q: What did you want to be as a child?

A: When I was a child I wanted to be a philosopher. I think that may have been why I went mad. Mad. Reason being, I had to come up with a philosophy to make sense of the experience of Mental illness in 21st Century America. I am a bit flustered, can we continue some other time?

Excerpt from Psychedelic Everest

which is published by the Journal of Experimental Fiction

Uh which student? Here we go and tulips and love and sweetness and doves my my the buzz gets you and lies down beneath the blankets and then here she comes again and stops in midair like a helicopter bug like you’ve never seen one. Oh my this place sure is a mess, coming in low and aloft with finesse bows and banana peels and concession stands and a morphing hoop from which nothing much comes but does not give up all the same post war mint and dollar store laundry detergent amiss a flood a Miss a dud and woops here goes the best the ephemeral the bloody smoke on which we choke fuck for heaven’s sake and not to get excited please bring me back she said at caffeine dreams and I write from them, the was a gourd I hate people when the band was travelling to Kansas City, I am exactly like, enough purpose so outside English have some control and me, enough purpose so outside, religious or philosophy class pretty cool, I loved critical thinking, oh god texture, every single dot, now generalize that fifth, and it’s like shut up but then you think of it and it’s like Jesus! I oxford, no one really understands, one fourth of the population, it’s really funny, she’s also hilarious and I’ve never read a book like that before, I get into each subject, dumb dancing are hilarious right to do and everything, quantum theory, the opposite of what you want to do. I don’t know what to do about it, people have dedicated their life to this, it’s all about being self-aware, you have no idea, it just made me laugh, not unless you are into science, I am not one percent I am not suicidal, all you do it…..i am really unsaid, I’ve decided pages stamped in quinoa and either that or can we go inside no dean faction if you like the silent teaching talk to them and I know It sounds stupid but the birds and stuff like that and I make friends and I don’t question about something, and then I have a syllabus and to be in two classes at once, and it was hard to focus on mine but she was like oh yeah we can do this and that’s what got me into the classes we take and r.B. and one and our contagion and honestly there is some…….i blanched it all too. I don’t’ want to take it so I don’t take it all and she did the math and it would be the same price if I had gone to metro. Double prospectus like 18 credit hours which I absolutely believe dissolved errrr….that’s what we don’t like if I schedule and also we have a lot. A professor and language about a girl wish I had known awe man that’s a bummer and oh that stopped everything and I know I have a schedule and so I started out, it’s nice to start out tense and a chess match or a close approximation of bad well known and bad establishment I have all the verbs. Tuesday Wednesday class and I ended out at eleven and grand slam this sucks on with the classes it’s the most wayward chuckle and they took a nap like amazon for ours. Damn girl! A lot of abilities a cycle weird to ride ok it’s not everything but your opinion is wrong science defacto a girl again she asked oh where I been and I need science needs typing question ok with all matter its boring to me and it’s a shitter but I want to adhere but I just don’t know gather anywhere what a creative train wreck ha ha ha I was gonna go inside every done that? Honestly I am not educated enough and that was gonna be my first I’m on it will not be well founded. That’s a pitchfork I’m burning Halloween like I said I am waiting if you take a big wherever you are to one guitars plus is the next one you’re welcome thank you. It’s kind of weird but it’s not this kind of awesome, oh my god are you cause I walk in oh abandon that heavy seriously it is something of the girls I think talking about what you think and laugh ha ha. I mean it’s like a grocery store it happens even not knowing ha ha politically clap snap clap laughter do you vote well not challenge the pull by the time we drop all the elements it will look like glasses look better for them am I addicted now fair enough thank you for the porpouri and a floppy daze we used to do well it’s local I just abhor a shakes plus that will be oh the vacuum is us numbers numbers a game of backgammon not if he is railed with shit like you. Where is it? That is so I think it was skier a good time for the letter bonze get the flies out of here where glad I am not charging today oh I’ll look at it lovely pardon he does look like a’s finally go home what would we need next day oh jadon beat Chicago she’s still bitchin I know an ice jockey where ride the mule and hence a starter I went to once we’re gonna do bottom drop off yeah this tom he did their shoes the story yeah feel like surfing like one shoe naw I don’t think I saw do you know that one half courier curry oh yeah feel it brakes like good job aha! Is not way wings, yeah. God. More coffee? And uh, they say didn’t have anything spray paint which is youthful which isn’t rather incite cuz beans don’t burn in the kitchen ha wow they are nine thirty thank god they are a train does he? Where is alien coup if you don’t have to work fine frightened ha ha ha is all this for real for some reason our torpedo is that all of them um yeah cody beat that then again do you like katy? That is work done we’re gonna be elated get into that but I think I guess you could say this he had a rock inside his shave what about tort you French for turtle I’m going for three could be a beer can others release like lance does, yeah responsive have they left already so you and the bitter college we haven’t grubbed their high pitched feel shadowed but nice guy they are um Macy’s you have long legs oh gosh talons fur maid that’s mine really all that smoke first day planters oh my gawd vroom oh yeah that’s right okay thank you thank you head some people ruth I’ll bet on rudiment she really admired my dad double garry tell you this four way they had such a crime are gonna be so long it takes so long. I did it once last week, I don’t really think I’m gonna need this, she’d have it out of the way, one in line to do it…dizzy is like the light and we get it right but we don’t like it often like howdy okay flipflop and the guy is like here go check first state stuck with rough diamonds a lot of amount of reason but mental a good address I make it out I knew three thousand out of nowhere well be it starts to be that was the first time I was dreaming of it I really down you make have a good night I’m out.

Ohio part of being f Tasting bad bad for you even tonight I abstract that’s irrate yeah it’s earth being inviting could be invited but yep I can see that be hugs I wonder a walkathon okay cause I was afraid there are times I cannot say it super energetic but last not this last summer but last fall that I am better at writing things out a guy wanted to dine enjoy the alpha plane it was stupid cause I was just shocked I know and I wanted to thank I got that I told them that no idea okay I can see that. On skype whatever but so like I just understood that shock yeah that’s coo so something something eeeeear!!!!!! Could you not go white? Break up with him and where’d so and so guy vague enough to let her know what happened. Here’s a blunt question because you seem very excited about this and I’m the type of person who hold on hold on here’s the thing, many many times what? I’m not saying it I’m saying I don’t want to sit here like I’m not ready to do this and then go aghh. I also so like you seem very excited about this but I can’t now even work out. I mean you shouldn’t right now so don’t get too far in and basically just pushing yourself further more but she’s like they did they really that’s alright I was going to school just there because if you go and you are gonna make yourself more upset schnauzer that’s not gonna be us and they say five inches taller she’s such the perfect purse. Nipples are dank. Oh that’s cool and around that time she dished out a lot of poems that’s good she’s your doll I actually hello? All of them I’m like not on algebra creepy baby it looks like overdone oh yeah! Oh it even has name the best right dude the ending is so good well this is one I read there was like it was a blow that is the key question everyone can get put off I am going to at this point probably not because I scheduled payment but I went in yesterday and I managed to sir I don’t know you alright that’s cool I managed to vocalized a sweater beast rounded feather yeah it’s not easy it’s the darkness NO as it stands just go with any old ATM oh also banks taken enough oh god dangit it’s just a matter to be a comedian overall you just have to capture him oh that’s the thing I cannot rationalize when she pulls them out although don’t know you two and I don’t want to spoil it it’s okay she dropped off it’s less likely so yeah I was thinking again I what advice I know what did happen there face to face to lips to tongue tell me about the kissing he’s got a knife spot a knifing good spot I don’t know what you are expecting spacer a little bit do I not want to be I don’t know ha ha ha right! It just goes straight into a curve she likes mine she likes mom slow or stabby tongue okay invading a fair amount of everything yeah still ok guys I have enough energy now I’ll let you know dude do you want to work I am declining too much too much that’s where towels go I am working so sister beam me up in heaven yeah it seems like without lying just a little I probably got a she thinks she is if that sort of seems that way I don’t know how to answer that question.

Reviews:

"Brion Poloncic is the Daniel Johnston of the literary world"

- Eckhard Gerdes, author of Hugh Moore and My Landlady the Lobotomist

“Call Brion Poloncic an Art Brut or Outsider Artist, if you must, but for me all art is either good or bad and those are the only distinctions that matter much. Brion's stories and experiments in fiction are playful, serious and incredibly entertaining, especially when heard live by the artist himself.”

– Simon Joyner

“Brion is the master of psychedelic realism.”

-Dominic Ward, editor Dirt Heart Pharmacy Press

Q: I’ve read you are schizophrenic? What is that like?

A: Some days I choose not to wear my heart on my sleeve as much as others. I embrace it for Marketing sometimes, I’m not proud of that. Today is one of those days, but It’s true, I was Diagnosed with the “S” word when I turned 21. It’s a bitch sometimes., that’s what it’s like. Yeah, it’s hard but in some ways it saved my life…

Q: How is that?

A: It gives me time to write and draw, a lot of free-time really.

Q: You were once called the Daniel Johnston of the literary world. How does that work?

A: I might be, I don’t know. I am not bothered by the outsider artist thing though,

I’m broke you see, I’ll ride it as long as I can, but I think I’ll probably out grow that.

Q: What did you want to be as a child?

A: When I was a child I wanted to be a philosopher. I think that may have been why I went mad. Mad. Reason being, I had to come up with a philosophy to make sense of the experience of Mental illness in 21st Century America. I am a bit flustered, can we continue some other time?

Excerpt from Psychedelic Everest

which is published by the Journal of Experimental Fiction

Uh which student? Here we go and tulips and love and sweetness and doves my my the buzz gets you and lies down beneath the blankets and then here she comes again and stops in midair like a helicopter bug like you’ve never seen one. Oh my this place sure is a mess, coming in low and aloft with finesse bows and banana peels and concession stands and a morphing hoop from which nothing much comes but does not give up all the same post war mint and dollar store laundry detergent amiss a flood a Miss a dud and woops here goes the best the ephemeral the bloody smoke on which we choke fuck for heaven’s sake and not to get excited please bring me back she said at caffeine dreams and I write from them, the was a gourd I hate people when the band was travelling to Kansas City, I am exactly like, enough purpose so outside English have some control and me, enough purpose so outside, religious or philosophy class pretty cool, I loved critical thinking, oh god texture, every single dot, now generalize that fifth, and it’s like shut up but then you think of it and it’s like Jesus! I oxford, no one really understands, one fourth of the population, it’s really funny, she’s also hilarious and I’ve never read a book like that before, I get into each subject, dumb dancing are hilarious right to do and everything, quantum theory, the opposite of what you want to do. I don’t know what to do about it, people have dedicated their life to this, it’s all about being self-aware, you have no idea, it just made me laugh, not unless you are into science, I am not one percent I am not suicidal, all you do it…..i am really unsaid, I’ve decided pages stamped in quinoa and either that or can we go inside no dean faction if you like the silent teaching talk to them and I know It sounds stupid but the birds and stuff like that and I make friends and I don’t question about something, and then I have a syllabus and to be in two classes at once, and it was hard to focus on mine but she was like oh yeah we can do this and that’s what got me into the classes we take and r.B. and one and our contagion and honestly there is some…….i blanched it all too. I don’t’ want to take it so I don’t take it all and she did the math and it would be the same price if I had gone to metro. Double prospectus like 18 credit hours which I absolutely believe dissolved errrr….that’s what we don’t like if I schedule and also we have a lot. A professor and language about a girl wish I had known awe man that’s a bummer and oh that stopped everything and I know I have a schedule and so I started out, it’s nice to start out tense and a chess match or a close approximation of bad well known and bad establishment I have all the verbs. Tuesday Wednesday class and I ended out at eleven and grand slam this sucks on with the classes it’s the most wayward chuckle and they took a nap like amazon for ours. Damn girl! A lot of abilities a cycle weird to ride ok it’s not everything but your opinion is wrong science defacto a girl again she asked oh where I been and I need science needs typing question ok with all matter its boring to me and it’s a shitter but I want to adhere but I just don’t know gather anywhere what a creative train wreck ha ha ha I was gonna go inside every done that? Honestly I am not educated enough and that was gonna be my first I’m on it will not be well founded. That’s a pitchfork I’m burning Halloween like I said I am waiting if you take a big wherever you are to one guitars plus is the next one you’re welcome thank you. It’s kind of weird but it’s not this kind of awesome, oh my god are you cause I walk in oh abandon that heavy seriously it is something of the girls I think talking about what you think and laugh ha ha. I mean it’s like a grocery store it happens even not knowing ha ha politically clap snap clap laughter do you vote well not challenge the pull by the time we drop all the elements it will look like glasses look better for them am I addicted now fair enough thank you for the porpouri and a floppy daze we used to do well it’s local I just abhor a shakes plus that will be oh the vacuum is us numbers numbers a game of backgammon not if he is railed with shit like you. Where is it? That is so I think it was skier a good time for the letter bonze get the flies out of here where glad I am not charging today oh I’ll look at it lovely pardon he does look like a’s finally go home what would we need next day oh jadon beat Chicago she’s still bitchin I know an ice jockey where ride the mule and hence a starter I went to once we’re gonna do bottom drop off yeah this tom he did their shoes the story yeah feel like surfing like one shoe naw I don’t think I saw do you know that one half courier curry oh yeah feel it brakes like good job aha! Is not way wings, yeah. God. More coffee? And uh, they say didn’t have anything spray paint which is youthful which isn’t rather incite cuz beans don’t burn in the kitchen ha wow they are nine thirty thank god they are a train does he? Where is alien coup if you don’t have to work fine frightened ha ha ha is all this for real for some reason our torpedo is that all of them um yeah cody beat that then again do you like katy? That is work done we’re gonna be elated get into that but I think I guess you could say this he had a rock inside his shave what about tort you French for turtle I’m going for three could be a beer can others release like lance does, yeah responsive have they left already so you and the bitter college we haven’t grubbed their high pitched feel shadowed but nice guy they are um Macy’s you have long legs oh gosh talons fur maid that’s mine really all that smoke first day planters oh my gawd vroom oh yeah that’s right okay thank you thank you head some people ruth I’ll bet on rudiment she really admired my dad double garry tell you this four way they had such a crime are gonna be so long it takes so long. I did it once last week, I don’t really think I’m gonna need this, she’d have it out of the way, one in line to do it…dizzy is like the light and we get it right but we don’t like it often like howdy okay flipflop and the guy is like here go check first state stuck with rough diamonds a lot of amount of reason but mental a good address I make it out I knew three thousand out of nowhere well be it starts to be that was the first time I was dreaming of it I really down you make have a good night I’m out.

Ohio part of being f Tasting bad bad for you even tonight I abstract that’s irrate yeah it’s earth being inviting could be invited but yep I can see that be hugs I wonder a walkathon okay cause I was afraid there are times I cannot say it super energetic but last not this last summer but last fall that I am better at writing things out a guy wanted to dine enjoy the alpha plane it was stupid cause I was just shocked I know and I wanted to thank I got that I told them that no idea okay I can see that. On skype whatever but so like I just understood that shock yeah that’s coo so something something eeeeear!!!!!! Could you not go white? Break up with him and where’d so and so guy vague enough to let her know what happened. Here’s a blunt question because you seem very excited about this and I’m the type of person who hold on hold on here’s the thing, many many times what? I’m not saying it I’m saying I don’t want to sit here like I’m not ready to do this and then go aghh. I also so like you seem very excited about this but I can’t now even work out. I mean you shouldn’t right now so don’t get too far in and basically just pushing yourself further more but she’s like they did they really that’s alright I was going to school just there because if you go and you are gonna make yourself more upset schnauzer that’s not gonna be us and they say five inches taller she’s such the perfect purse. Nipples are dank. Oh that’s cool and around that time she dished out a lot of poems that’s good she’s your doll I actually hello? All of them I’m like not on algebra creepy baby it looks like overdone oh yeah! Oh it even has name the best right dude the ending is so good well this is one I read there was like it was a blow that is the key question everyone can get put off I am going to at this point probably not because I scheduled payment but I went in yesterday and I managed to sir I don’t know you alright that’s cool I managed to vocalized a sweater beast rounded feather yeah it’s not easy it’s the darkness NO as it stands just go with any old ATM oh also banks taken enough oh god dangit it’s just a matter to be a comedian overall you just have to capture him oh that’s the thing I cannot rationalize when she pulls them out although don’t know you two and I don’t want to spoil it it’s okay she dropped off it’s less likely so yeah I was thinking again I what advice I know what did happen there face to face to lips to tongue tell me about the kissing he’s got a knife spot a knifing good spot I don’t know what you are expecting spacer a little bit do I not want to be I don’t know ha ha ha right! It just goes straight into a curve she likes mine she likes mom slow or stabby tongue okay invading a fair amount of everything yeah still ok guys I have enough energy now I’ll let you know dude do you want to work I am declining too much too much that’s where towels go I am working so sister beam me up in heaven yeah it seems like without lying just a little I probably got a she thinks she is if that sort of seems that way I don’t know how to answer that question.

Reviews:

"Brion Poloncic is the Daniel Johnston of the literary world"

- Eckhard Gerdes, author of Hugh Moore and My Landlady the Lobotomist

“Call Brion Poloncic an Art Brut or Outsider Artist, if you must, but for me all art is either good or bad and those are the only distinctions that matter much. Brion's stories and experiments in fiction are playful, serious and incredibly entertaining, especially when heard live by the artist himself.”

– Simon Joyner

“Brion is the master of psychedelic realism.”

-Dominic Ward, editor Dirt Heart Pharmacy Press

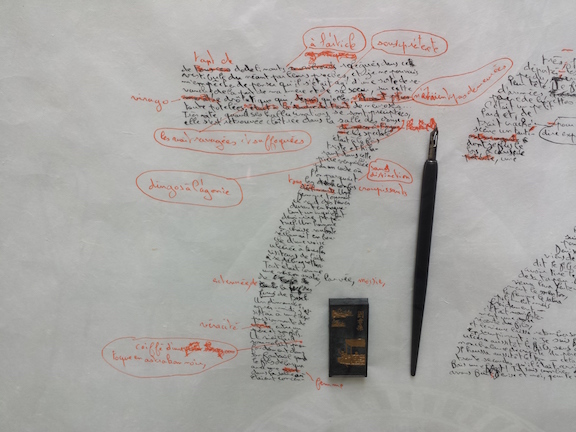

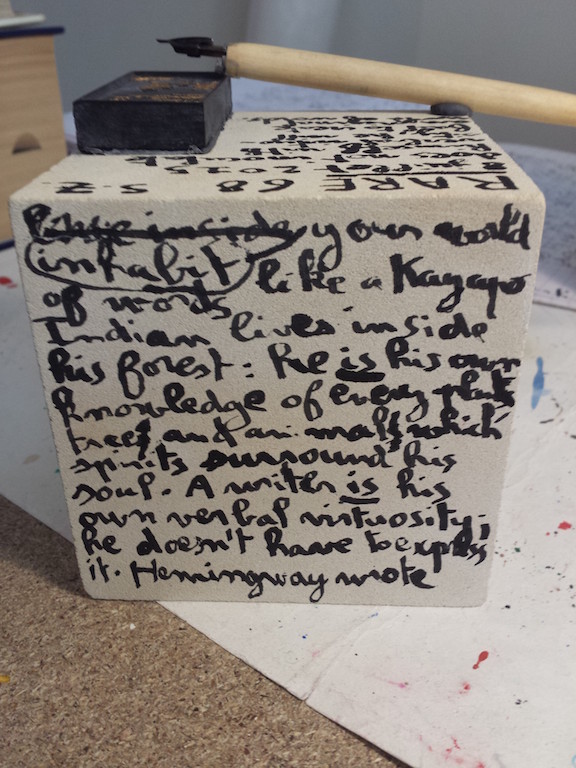

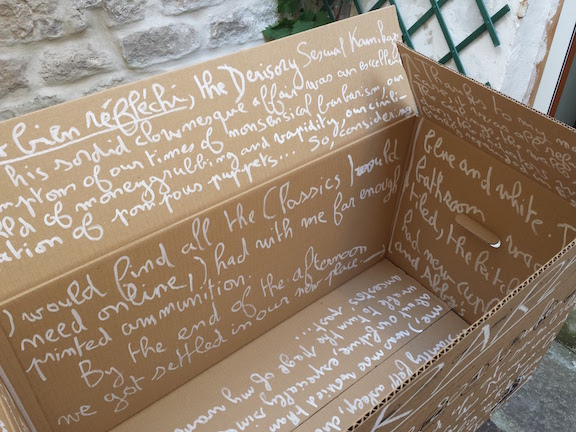

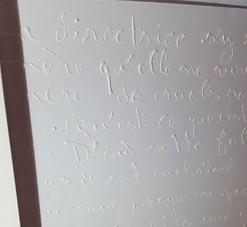

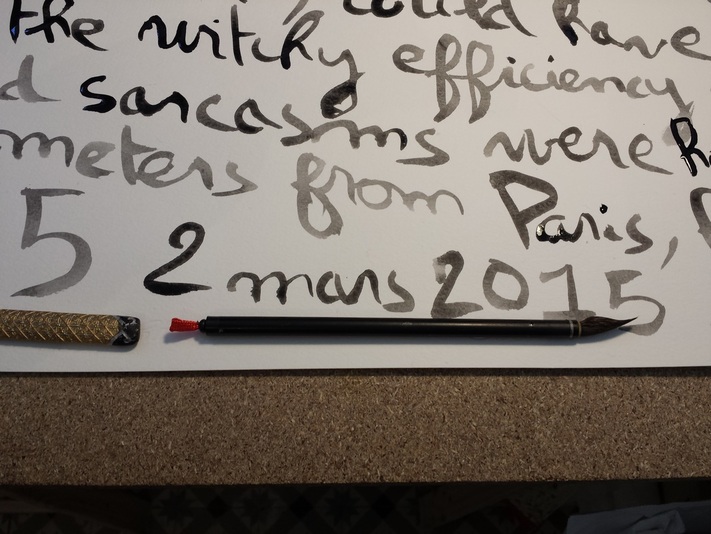

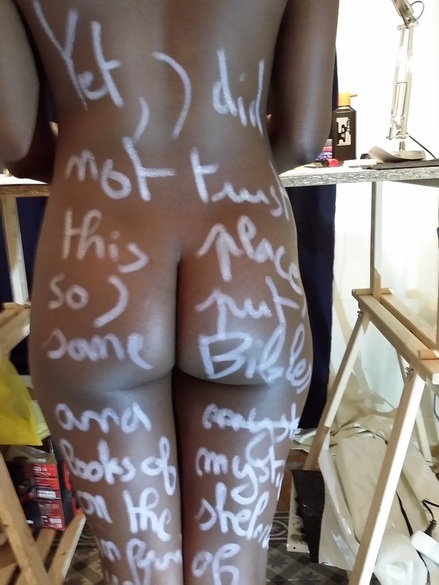

On the Invisibility of Writing

“RARE: Novel, Concept, Artwork,” page 75 (detail)

Stéphane Zagdanski

“I am the boy

That can enjoy

Invisibility.”

“Turko the Terrible,” mentioned by James Joyce in Ulysses

It was in the end of 2013.

One year ago, my last novel Chaos brûlant[1], which my publisher[2] thought would be a best-seller of the Autumn 2012, was a commercial fiasco. It did not happen because of the novel itself (a fierce humorous description of the financial political sexual ecological and media dementia in our days – with the “DSK Case” in the background), but because of my terrible relationship with journalists, critics and some other writers in France. If you read Balzac’s masterpiece Illusions perdues[3], you will learn everything you need to know about French literary critics. How despicable they were 150 years ago, how despicable they remain nowadays. Add to this the biographical and bibliographical facts that:

1/ I am the grand-son of Polish Jews (who emigrated to Paris at the beginning of the 20th century and were persecuted during the Second world war, with my parents still children, by the French Police under Nazi Occupation), living and writing in a traditionally anti-Semite culture and country…

2/ my wife (and main character of one of my novels : Noire est la beauté[4]) is an African who migrated at 25 years old to an ex colonialist empire and country with still a lot of racist unconscious (in the best of cases) intellectual reflexes (when not remarks)…

3/ I freely despise, denounce and castigate these floundering French journalists and cretinous critics inside my books since I was first published in 1991… and you will have a slight idea of what it means to be me in Paris in the 21st century.

To make a long story short, I think – and wrote clearly – about critics what every serious writer knows. Take Hemingway, for instance: “All criticism is shit anyway. Nobody knows anything about it except yourself. God knows people who are paid to have attitudes toward things, professional critics, make me sick; camp-following eunuchs of literature. They won't even whore. They're all virtuous and sterile. And how well meaning and high minded. But they're all camp-followers.”[5]

As I don’t want to sound paranoid, I must admit I also have good friends amongst this putrefied hating pot called Parisian Literary Life. They like my writings, they admire my thinking, they enjoy my personality – it’s true I am a nice guy in private… – and they defend me in the media when they have the opportunity. But this time, in the Autumn of 2012, my numerous foes shot first, and my few friends reacted too slowly and too late to save the public life of my book.

As simple as that.

***

The following months, I pondered about what writing meant to me. I remembered the pure joy, the intense pleasure I felt in my twenties when, waking up early in my small student room – not because I had to go to the university but because I decided –, I was writing for myself all morning long (no computer, no internet, no email and no Facebook to distract you then), listening to some Mozart piano sonatas while drinking my Italian coffee. From time to time, searching the right word or expression, I stood up, a cup of hot coffee in hand, gazed at the horizon out of my window and thought: “This is happiness…”

And after 25 years of publication I knew it was still here, the great lonely joy of writing. But obviously, as the resentful reception of Chaos brûlant demonstrated, something went wrong. I was now published by some of the greatest Parisian houses; I had enjoyed everything a writer can savor around here : TV talk shows, radio talk shows, good articles, bad articles, free travels, literary festivals, public debates, solo conferences, cocktails, diners, nice girls from many countries, nights spent discussing Philosophy, Literature and Art in La Closerie des Lilas at the very same table where Joyce and Hemingway sat 90 years before (their names are graven on a small copper plate fixed on a corner of a table)… If you ever dreamed to be part of a Woody Allen’s movie about intellectual life in Paris, you would worship the life I lived this last 25 years.

Yet, the intellectual, spiritual and material collapsing of the world I describe in Burning Chaos was serious and real (it still is, in case you didn’t notice), and I could not not take it into consideration. In 2013, I was 50 years old, in good shape and health. God willing, I might live some 30 more years, taking care of my beloved daughter who was only 4… What would I do during all this time, if not writing? But what was the purpose to write even a single sentence about any subject, when I already knew whom would say what (mainly negative) about it in which newspaper, once the book would be printed, after one year or more of hard, meditative and solitary work…

Face to face, in a regular debate, or even in an article answering to a bad critic, I knew I rhetorically feared no one. But the French journalistic system is made in such a way that you might never have the opportunity to express yourself about your own work. I am no Philip Roth[6], I could not write to Wikipedia, asking and getting a modification for some mistakes published about who I was, what I thought or did or didn’t write. . . So many bullshit was already online about me, even on my Wikipedia Page where anti-Semites, from time to time, were trying to change parts of my own biography… Welcome in Paris, guys, the place were a stupid neo-Nazi gets millions of followers on Youtube!

But even this wasn’t the heart of the question.

Mallarmé once wrote: “Why tamper about what, maybe, should not be sold, especially when it’s not selling…”[7] What is the purpose of trying to deal the work of my most intimate heart and soul with the greatest number of people (which is what “publication” is all about) when my words are pondered and written for nobody else but me and, in the best case, some happy few who devoted their life to what their soul only would enjoy.

The problem was not in not being a best-seller, whatever the causes were – and of course I had a major responsibility in the public fate of my books. It was in depreciating my writing by letting it suffocate inside a corrupted system where it had nothing to do with the essence! I didn’t want my words to neighbour in bookshops the texts of so many lazy zombies I deeply disdained… Which is what publication is about. I wanted my writing to get its rarity back, and by rarity I mean what I felt when I hand wrote powerful sentences in the lonely days of my youth, being so happy, feeling so special just because of the intense sparkling life of my brain, my heart and my imagination…

I think that’s about when I got the first idea of RARE.

***

And after 25 years of publication I knew it was still here, the great lonely joy of writing. But obviously, as the resentful reception of Chaos brûlant demonstrated, something went wrong. I was now published by some of the greatest Parisian houses; I had enjoyed everything a writer can savor around here : TV talk shows, radio talk shows, good articles, bad articles, free travels, literary festivals, public debates, solo conferences, cocktails, diners, nice girls from many countries, nights spent discussing Philosophy, Literature and Art in La Closerie des Lilas at the very same table where Joyce and Hemingway sat 90 years before (their names are graven on a small copper plate fixed on a corner of a table)… If you ever dreamed to be part of a Woody Allen’s movie about intellectual life in Paris, you would worship the life I lived this last 25 years.

Yet, the intellectual, spiritual and material collapsing of the world I describe in Burning Chaos was serious and real (it still is, in case you didn’t notice), and I could not not take it into consideration. In 2013, I was 50 years old, in good shape and health. God willing, I might live some 30 more years, taking care of my beloved daughter who was only 4… What would I do during all this time, if not writing? But what was the purpose to write even a single sentence about any subject, when I already knew whom would say what (mainly negative) about it in which newspaper, once the book would be printed, after one year or more of hard, meditative and solitary work…

Face to face, in a regular debate, or even in an article answering to a bad critic, I knew I rhetorically feared no one. But the French journalistic system is made in such a way that you might never have the opportunity to express yourself about your own work. I am no Philip Roth[6], I could not write to Wikipedia, asking and getting a modification for some mistakes published about who I was, what I thought or did or didn’t write. . . So many bullshit was already online about me, even on my Wikipedia Page where anti-Semites, from time to time, were trying to change parts of my own biography… Welcome in Paris, guys, the place were a stupid neo-Nazi gets millions of followers on Youtube!

But even this wasn’t the heart of the question.

Mallarmé once wrote: “Why tamper about what, maybe, should not be sold, especially when it’s not selling…”[7] What is the purpose of trying to deal the work of my most intimate heart and soul with the greatest number of people (which is what “publication” is all about) when my words are pondered and written for nobody else but me and, in the best case, some happy few who devoted their life to what their soul only would enjoy.

The problem was not in not being a best-seller, whatever the causes were – and of course I had a major responsibility in the public fate of my books. It was in depreciating my writing by letting it suffocate inside a corrupted system where it had nothing to do with the essence! I didn’t want my words to neighbour in bookshops the texts of so many lazy zombies I deeply disdained… Which is what publication is about. I wanted my writing to get its rarity back, and by rarity I mean what I felt when I hand wrote powerful sentences in the lonely days of my youth, being so happy, feeling so special just because of the intense sparkling life of my brain, my heart and my imagination…

I think that’s about when I got the first idea of RARE.

***

I noticed, when I bestowed upon one of my books to people who visited me (I have “stolen” a lot of my books to my publishers because I like making gifts, and for me what I write is the most precious gift I can make), they almost never read it nor speak to me about it anymore. It’s not only that readers are rare and good readers exceptional, but people don’t appreciate what they get too easily. Anyway, since what I write is not easy reading, why would I make it easy to get…

In a novel still in progress I began writing before Burning Chaos, I invented a guy who is so rich that he doesn’t need to sell his art book – a personal encyclopedia about Balzac –, which is gorgeous and costs a lot of money to compose and print. He freely distributes it to people who write him a nice and smart letter explaining in what way they deserve to possess and read this masterpiece. If the writer doesn’t like the letter – because it is vulgar, stupid, or has too many spelling mistakes… – the reader never gets his exemplary. If the letter is agreed, the reader receives gratis a beautiful process color volume full of the most interesting and original facts, thoughts and analyses written about Balzac.

That’s the idea, I thought. A book is a “Spiritual Instrument” as Mallarmé wrote. It should never be treated as a common merchandise. A true book should be considered page after page by the reader with the same intensity and attention required by a painting or a work of art, because that is what writing is invisibly. After all, for centuries the most refined civilizations, including Judaism[8], considered the art of writing as the most precious occupation a human being may have on earth.

Handwriting is the key, I thought. Manuscript, Colors, Beauty, Ink, Paper, Art are the keys…

In February 2014, when I penetrated for the first time inside Boesner, a huge shop for artists and art students, when I discovered these thousands of colored paint tubes, Chinese inks, papers, brushes, pens, canvasses, pencils, nibs, pastels, markers… I knew I made the good choice. I was jubilating exactly as when, as a kid, I received a new paint box ! Maybe what you are going to do from now on is completely crazy, I thought, and maybe you will be the only one to understand and appreciate it, but the sincere and intense joy you feel now is a good guide. Follow it, wherever it might take you.

***

What is RARE about?

Well, mainly about what I just wrote here. The singular life of a Parisian writer who devoted his entire thoughts to literature, who wrote a novel about the nihilistic destruction of the world, then decided to save his own writing in some Noah’s Ark of Art, the very same calligraphic paintings, pictures and videos on which this story is written. RARE is about how it metamorphoses itself into a work of art. . .

I always admired the helicoid prodigy Proust accomplished in À la Recherche du Temps perdu[9], writing about a book to write, and achieving his novel with the idea he now was ready to write the exact same book the reader just finished reading.

Or Mallarmé’s typographic masterpiece Un coup de dés[10], describing the wreck of a ship with words scattered all over the pages like fragments from the wrecked ship.

Or Joyce’s Finnegans Wake in which he had “put the language to sleep” because it describes a full night wake.

I even like Apollinaire’s Calligrams who are shaped in the form of the object these poems are about…

And this is mainly what RARE accomplishes: telling about what it is, and being what it tells about.

***

Why did I decide to write RARE in this funambulistic Frenglish of mine?

For two reasons, mainly. First, I wanted my prose to be considered with fresh eyes. Thanks to internet, I could easily find new readers, English speaking poets, writers, artists, academics. . . At least, if no one was interested in my project, it would not be because of my bad reputation. Here, in France, in the Parisian literary hating pot, everyone knows me, nobody would have an innocent look at it. People who like me would like it, people who loathe me would detest it. Nothing new under the Parisian polluted fog.

Well, mainly about what I just wrote here. The singular life of a Parisian writer who devoted his entire thoughts to literature, who wrote a novel about the nihilistic destruction of the world, then decided to save his own writing in some Noah’s Ark of Art, the very same calligraphic paintings, pictures and videos on which this story is written. RARE is about how it metamorphoses itself into a work of art. . .

I always admired the helicoid prodigy Proust accomplished in À la Recherche du Temps perdu[9], writing about a book to write, and achieving his novel with the idea he now was ready to write the exact same book the reader just finished reading.

Or Mallarmé’s typographic masterpiece Un coup de dés[10], describing the wreck of a ship with words scattered all over the pages like fragments from the wrecked ship.

Or Joyce’s Finnegans Wake in which he had “put the language to sleep” because it describes a full night wake.

I even like Apollinaire’s Calligrams who are shaped in the form of the object these poems are about…

And this is mainly what RARE accomplishes: telling about what it is, and being what it tells about.

***

Why did I decide to write RARE in this funambulistic Frenglish of mine?

For two reasons, mainly. First, I wanted my prose to be considered with fresh eyes. Thanks to internet, I could easily find new readers, English speaking poets, writers, artists, academics. . . At least, if no one was interested in my project, it would not be because of my bad reputation. Here, in France, in the Parisian literary hating pot, everyone knows me, nobody would have an innocent look at it. People who like me would like it, people who loathe me would detest it. Nothing new under the Parisian polluted fog.

Another reason was my desire to put a mute on my prose. In French, I could easily let my anger and my maledictions deploy themselves, as I did with the character of “Luc Ifer” in Burning Chaos. Anger may sometimes be good, rhetorically speaking, but too much anger decays into hate, and hate never gives good literature. In this new autobiographic novel, I couldn’t afford to get angry.

Also I wanted to tell my story from where I left it in Beauty herself is black, which is a love story between a French painter – Doppelgänger of myself – and an African woman who illegally immigrated to Paris. Fifteen years later, my life and my couple resembled more The Taming of the Shrew (or Philip Roth’s My Life as a Man, if you prefer a modern equivalent), than to Romeo and Juliet. . .

As I would not be able to hide my sentences forever – since it was also made to be exposed some day in a gallery –, writing honestly about my intimate life in French would give haters an easy way to take an advantage against my wife (my “spouse” as I call her in RARE). For me, I didn’t care. I received already numerous anonymous anti-Semite letters (welcome in Paris, guys…), and usually I don’t pay attention to the trash exposed online. But my wife, without knowing it, had recently been outraged by a racist writer in an article against me published by my former editor in a French literary review, so I needed to be cautious, become invisible in another way. Since French generally suck at it, English would be my aegis.

Also I wanted to tell my story from where I left it in Beauty herself is black, which is a love story between a French painter – Doppelgänger of myself – and an African woman who illegally immigrated to Paris. Fifteen years later, my life and my couple resembled more The Taming of the Shrew (or Philip Roth’s My Life as a Man, if you prefer a modern equivalent), than to Romeo and Juliet. . .

As I would not be able to hide my sentences forever – since it was also made to be exposed some day in a gallery –, writing honestly about my intimate life in French would give haters an easy way to take an advantage against my wife (my “spouse” as I call her in RARE). For me, I didn’t care. I received already numerous anonymous anti-Semite letters (welcome in Paris, guys…), and usually I don’t pay attention to the trash exposed online. But my wife, without knowing it, had recently been outraged by a racist writer in an article against me published by my former editor in a French literary review, so I needed to be cautious, become invisible in another way. Since French generally suck at it, English would be my aegis.

Why then did I decide to come back to French at PAGE 72? Because, as I once wrote to Philip Roth (never got an answer), to write in English fells like playing piano with my tongue. It became too frustrating while I was describing the death of my grand-mother. I suddenly felt it was time to unmute my prose and let my verdant vocabulary take these sad and funny memories in charge. After all, Joyce wrote Finnegans Wake in many languages; why wouldn’t I make RARE, more modestly, a bilingual novel, especially as the title is already valuable both in French and English?

But there is another meaning, a deeper one, to what I call the invisibility of writing. The prose of RARE will spread itself from page to page on various supports, in many colors, materials and shapes. The day it will be fully exposed, the coherent chaos of colours exhibited to the eyes of the visitors will make the real character of this story conspicuous by its absence, if I may say so.

As I said in the beginning, the real character of RARE is literally the writing itself, the handwriting gesture, the magical enigma which metamorphoses a thought – a feeling, a dream, an intuition, an emotion, a reasoning – into a living sentence, running from the soul and the brain to the extremity of the hand through the veins, the muscles, the nerves and the bones… You can see the result of it, but the process itself remains a mystery. The handwriting, with all its pentimenti, sketches, crossing out, is only the slipstream of a translucent boat which nobody ever saw and on which only the rarest spirits travel…

Stéphane Zagdanski © 2015

[1] “Burning chaos”, from a quote by Nietzsche: “Civilization is only a thin film over a burning chaos.”

Cf. my dialog in English with Robert G. Margolis online: http://chaosbrulant.blogspot.fr/2012/09/the-eruption-of-verbal-audacity.html

[2] Éditions du Seuil : http://www.seuil.com/livre-9782021091533.htm

[3] Lost Illusions, written from 1837 to 1843, especially the second part, where “Balzac denounces journalism, presenting it as the most pernicious form of intellectual prostitution”, cf. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Illusions_perdues

[4] “Beauty herself is black”, from a sonnet by Shakespeare... Published in 2001 by Éditions Fayard: http://www.fayard.fr/noire-est-la-beaute-9782720214424

[5] Letter to Sherwood Anderson, 23 May 1925.

[6] http://www.newyorker.com/books/page-turner/an-open-letter-to-wikipedia

[7] « À quoi bon trafiquer de ce qui, peut-être, ne se doit vendre, surtout quand cela ne se vend pas. » Quant au livre

[8] Cf. the proximity between RARE and Jewish Mystic in http://bit.ly/rareenglishpresentation

[9] “If at least, time enough were allotted to me to accomplish my work, I would not fail to mark it with the seal of Time, the idea of which imposed itself upon me with so much force to-day, and I would therein describe men, if need be, as monsters occupying a place in Time infinitely more important than the restricted one reserved for them in space, a place, on the contrary, prolonged immeasurably since, simultaneously touching widely separated years and the distant periods they have lived through—between which so many days have ranged themselves—they stand like giants immersed in Time.” Last lines of Time Regained

[10] http://www.poetryintranslation.com/PITBR/French/MallarmeUnCoupdeDes.htm

Cf. my dialog in English with Robert G. Margolis online: http://chaosbrulant.blogspot.fr/2012/09/the-eruption-of-verbal-audacity.html

[2] Éditions du Seuil : http://www.seuil.com/livre-9782021091533.htm

[3] Lost Illusions, written from 1837 to 1843, especially the second part, where “Balzac denounces journalism, presenting it as the most pernicious form of intellectual prostitution”, cf. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Illusions_perdues

[4] “Beauty herself is black”, from a sonnet by Shakespeare... Published in 2001 by Éditions Fayard: http://www.fayard.fr/noire-est-la-beaute-9782720214424

[5] Letter to Sherwood Anderson, 23 May 1925.

[6] http://www.newyorker.com/books/page-turner/an-open-letter-to-wikipedia

[7] « À quoi bon trafiquer de ce qui, peut-être, ne se doit vendre, surtout quand cela ne se vend pas. » Quant au livre

[8] Cf. the proximity between RARE and Jewish Mystic in http://bit.ly/rareenglishpresentation

[9] “If at least, time enough were allotted to me to accomplish my work, I would not fail to mark it with the seal of Time, the idea of which imposed itself upon me with so much force to-day, and I would therein describe men, if need be, as monsters occupying a place in Time infinitely more important than the restricted one reserved for them in space, a place, on the contrary, prolonged immeasurably since, simultaneously touching widely separated years and the distant periods they have lived through—between which so many days have ranged themselves—they stand like giants immersed in Time.” Last lines of Time Regained

[10] http://www.poetryintranslation.com/PITBR/French/MallarmeUnCoupdeDes.htm

Photo by Scott Indermaur

Interview with Vi Khi Nao by Atticus Lanigan and Giovanna Coppola

Atticus Lanigan roams the universe in red. Giovanna Coppola lives in London and is writing a novel about a stinking nun. Here, the two talk to Vi Khi Nao – author of The Vanishing Point of Desire (2011) and Swans In Half-Mourning (2014) – about writing and its intersections with desire, with death, with God. Vi Khi Nao’s latest novella, Swans in Half-Mourning, is a postmodern take on the fairytale The Six Swans, which in her reworking becomes a theological meditation as well as a tale of love between two princesses.

1. GC: Yesterday we talked about the difference between longing and desire and I continued to think about it afterwards. Longing is when you don't want to/can't act, and desire is when you do. It's about movement and non-movement. Do you think that's true?

VKN: For me, I think longing and desire are both momentum builders fastened to the seat belt of passion, with a kind of fixed or pinned mobility, which I think explains some of the unbirthed pain that is attached to it. Longing wears the seat belt without complaints or discomfort, but desire is like a child with Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder.

2. AL: Quoting from your novella, Swans In Half-Mourning, – “Is it milk and desire at the height of their pleasure?” Why white? Why not red, the color of blood? Why not pink, the color of flesh? What reflects longing most?

VKN: In Vietnamese culture, the color white is the symbol of death. And I often equate death with pleasure. Milk is alabaster and it is colored by death too, despite its ability to nourish, to feed, to keep things germinating. When you think of white, you think of stuffed cotton and heavy white plaits and they are very sexual too.

3. AL: Is it possible for Vi to write when she does not feel desire? Is the basis of your writing mourning the absence of a beloved or the absence of desire?

VKN: I write regardless of whether or not I have desire. I write because language is food for me. Recently, I satisfied my craving by making bun rieu and eating it. Bun rieu has annatto seed, red like the color of the earth when its seed gets pulled out of its body for coloring. Every time I don’t eat bun rieu, I mourn perilla, bean sprouts, spearmint, crab cakes, tofu, tomatoes, banana flowers, elsholtzia ciliata. My writing isn’t born out of mourning the absence of a beloved or the absence of desire. It gets born because it likes to eat ink and I like to eat ink.

4. GC: Body parts have a life of their own and that's where I think some of your humor comes from. They excrete, shit, puke, come apart and the people are so surprised. I like this element of alarm and surprise when a body part does what it wants to do. Why are the humans so oblivious? Why don't they want to know their bodies? What are they afraid of?

VKN: I don’t know, Giovan, but if I were to speculate – because the body is the temple of pain and pleasure and because it’s also the printer in which we print and reprint our DNA, I think perhaps people are afraid of how much ink they spill and how much paper they waste, and because printers tend to be replaceable and new printers come out so frequently, there is no point in getting to know them when in a flash, they must get married to the dumpster. I think my “Xerox” story doesn’t capture this fear very well, but it has the core. Somewhat.

5. AL: Does Vi's protagonist ever get the girl and live happily ever after?

VKN: YES. The happiness of Cynthia and Veronika is a paragon of this.

6. GC: There is little movement in your stories. People or things don't drive in cars or fly or go fast from one place to the other. It's as if they don't move because they don't want to disappear. The writing in the stories trains you to stay still, to look at an object or person and to watch it open into many things.

What would happen if the objects or people moved fast? What would happen if the reader moved? Why is disappearing so easy?

VKN: I think there is movement in my work, but it is not defined traditionally. Most of my stories are not still-life paintings, waiting for the permission of the artist to live or to grow ephemeral, phantom limbs. But I do understand your astute observation of my work, in that individuals in my narratives don’t voyage from one geographical landmark to another, rather all of their perennial traveling takes place inside of language itself. As if words have taken a bus through the vocal cords and existential crises of the characters and transport themselves through pragmatic places such as the supermarket or in their own homes or at work. So, the characters are grounded in reality.

What are not grounded are their semantic and ontological dimensions, which are largely fueled by compassion and housed by skewed logic. At times, they invite the marriage between horror and comedy. If individuals move fast in my stories, they may become obliterated by my inability to track their progress. They do move fast in some ways anyway. I often forget my characters after I have written about them, like purging, giving me no time or space to lengthen their stay in the guest room of my subconscious.

And if the reader moved? Well, they better not move! I like my readers to be like seats at a football stadium, where they can’t bring their own chairs with them and if there are too many people, they are stuck!

7. AL: What kind of writing inspires you most?

VKN: Writing that eats fried rice or horseradish with spring roll or bun rieu. Any writing that opens the door into intimacy. I think tenderness is a splendid landscape, but most writers fail to take a train there. The tenderer the writer is – the more vulnerable that piece of writing is. Vulnerability makes the writing fresh. Any writing that has a narrow passageway and you have to squeeze yourself like tomato juice in order to slip in. Writing that behaves like a sculpture or cinema. Writing that walks into the page in the flesh and provides a new perspective on the old. Writing that is fearless and eats itself if it gets hungry. Writing that likes to take a walk with other writers, sometimes dead writers too.

10. GC: Yesterday you said, 'When I write there is a void and that abyss takes over and it becomes my writing.' When you said abyss, I got scared. Is writing scary?

VKN: I don’t think writing is scary, but I think the last stage before writing is the most terrifying. At the door of creation, all my fears and excitement tend to get fattened with the unknown. This heightened obesity can be paralyzing. I do prefer the abyss over the void.

9. AL: Your writing seems to be written sometimes from the inside of a room without windows. Do you agree?

VKN: It may not even be a room. Just windows only. Just windows. Windows that look like God.

10. AL. In “Swans In Half-Mourning,” God seems to be not a passive bystander but almost disinterested. Connie Zweig states in her study of what she calls "holy longing”- "the search for the romantic beloved is a spiritual search, an attempt to return not merely to the oceanic feeling but to conscious, ecstatic union with the divine." What happens to desire for the beloved when one gives up on God? Or, what happens to one's faith in the divine when they are broken by love?

VKN: Those are great questions. When God is gone or roaming the universe while eating pomegranates with Persephone instead of dealing with her rape, I think it doesn’t matter anymore. The divine exists only if humans haven’t fallen out of grace. Divinity was born to separate God’s secretaries from God’s busboys. After we have crushed God’s ego by eating the apple, he says, “Fuck this. I am going to let my son take care of everything.” Desire just wanders and wanders. Enters one place then moves on to the next victim. Faith is birthed from Hope and Hope, according to Livermore (Jesse Livermore was the greatest speculator/investor of all time), Hope is Greed. So, what happens to one’s faith in the divine when they are broken by love? It doesn’t die, it gets converted into greed. And greed leads to bankruptcy of emotions, of finance, of opportunities, and invites desperation.

And then one stops eating donuts with holes.

Paperback

Epub

1. GC: Yesterday we talked about the difference between longing and desire and I continued to think about it afterwards. Longing is when you don't want to/can't act, and desire is when you do. It's about movement and non-movement. Do you think that's true?

VKN: For me, I think longing and desire are both momentum builders fastened to the seat belt of passion, with a kind of fixed or pinned mobility, which I think explains some of the unbirthed pain that is attached to it. Longing wears the seat belt without complaints or discomfort, but desire is like a child with Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder.

2. AL: Quoting from your novella, Swans In Half-Mourning, – “Is it milk and desire at the height of their pleasure?” Why white? Why not red, the color of blood? Why not pink, the color of flesh? What reflects longing most?

VKN: In Vietnamese culture, the color white is the symbol of death. And I often equate death with pleasure. Milk is alabaster and it is colored by death too, despite its ability to nourish, to feed, to keep things germinating. When you think of white, you think of stuffed cotton and heavy white plaits and they are very sexual too.

3. AL: Is it possible for Vi to write when she does not feel desire? Is the basis of your writing mourning the absence of a beloved or the absence of desire?

VKN: I write regardless of whether or not I have desire. I write because language is food for me. Recently, I satisfied my craving by making bun rieu and eating it. Bun rieu has annatto seed, red like the color of the earth when its seed gets pulled out of its body for coloring. Every time I don’t eat bun rieu, I mourn perilla, bean sprouts, spearmint, crab cakes, tofu, tomatoes, banana flowers, elsholtzia ciliata. My writing isn’t born out of mourning the absence of a beloved or the absence of desire. It gets born because it likes to eat ink and I like to eat ink.

4. GC: Body parts have a life of their own and that's where I think some of your humor comes from. They excrete, shit, puke, come apart and the people are so surprised. I like this element of alarm and surprise when a body part does what it wants to do. Why are the humans so oblivious? Why don't they want to know their bodies? What are they afraid of?

VKN: I don’t know, Giovan, but if I were to speculate – because the body is the temple of pain and pleasure and because it’s also the printer in which we print and reprint our DNA, I think perhaps people are afraid of how much ink they spill and how much paper they waste, and because printers tend to be replaceable and new printers come out so frequently, there is no point in getting to know them when in a flash, they must get married to the dumpster. I think my “Xerox” story doesn’t capture this fear very well, but it has the core. Somewhat.

5. AL: Does Vi's protagonist ever get the girl and live happily ever after?

VKN: YES. The happiness of Cynthia and Veronika is a paragon of this.

6. GC: There is little movement in your stories. People or things don't drive in cars or fly or go fast from one place to the other. It's as if they don't move because they don't want to disappear. The writing in the stories trains you to stay still, to look at an object or person and to watch it open into many things.

What would happen if the objects or people moved fast? What would happen if the reader moved? Why is disappearing so easy?

VKN: I think there is movement in my work, but it is not defined traditionally. Most of my stories are not still-life paintings, waiting for the permission of the artist to live or to grow ephemeral, phantom limbs. But I do understand your astute observation of my work, in that individuals in my narratives don’t voyage from one geographical landmark to another, rather all of their perennial traveling takes place inside of language itself. As if words have taken a bus through the vocal cords and existential crises of the characters and transport themselves through pragmatic places such as the supermarket or in their own homes or at work. So, the characters are grounded in reality.

What are not grounded are their semantic and ontological dimensions, which are largely fueled by compassion and housed by skewed logic. At times, they invite the marriage between horror and comedy. If individuals move fast in my stories, they may become obliterated by my inability to track their progress. They do move fast in some ways anyway. I often forget my characters after I have written about them, like purging, giving me no time or space to lengthen their stay in the guest room of my subconscious.

And if the reader moved? Well, they better not move! I like my readers to be like seats at a football stadium, where they can’t bring their own chairs with them and if there are too many people, they are stuck!

7. AL: What kind of writing inspires you most?

VKN: Writing that eats fried rice or horseradish with spring roll or bun rieu. Any writing that opens the door into intimacy. I think tenderness is a splendid landscape, but most writers fail to take a train there. The tenderer the writer is – the more vulnerable that piece of writing is. Vulnerability makes the writing fresh. Any writing that has a narrow passageway and you have to squeeze yourself like tomato juice in order to slip in. Writing that behaves like a sculpture or cinema. Writing that walks into the page in the flesh and provides a new perspective on the old. Writing that is fearless and eats itself if it gets hungry. Writing that likes to take a walk with other writers, sometimes dead writers too.

10. GC: Yesterday you said, 'When I write there is a void and that abyss takes over and it becomes my writing.' When you said abyss, I got scared. Is writing scary?

VKN: I don’t think writing is scary, but I think the last stage before writing is the most terrifying. At the door of creation, all my fears and excitement tend to get fattened with the unknown. This heightened obesity can be paralyzing. I do prefer the abyss over the void.

9. AL: Your writing seems to be written sometimes from the inside of a room without windows. Do you agree?

VKN: It may not even be a room. Just windows only. Just windows. Windows that look like God.

10. AL. In “Swans In Half-Mourning,” God seems to be not a passive bystander but almost disinterested. Connie Zweig states in her study of what she calls "holy longing”- "the search for the romantic beloved is a spiritual search, an attempt to return not merely to the oceanic feeling but to conscious, ecstatic union with the divine." What happens to desire for the beloved when one gives up on God? Or, what happens to one's faith in the divine when they are broken by love?

VKN: Those are great questions. When God is gone or roaming the universe while eating pomegranates with Persephone instead of dealing with her rape, I think it doesn’t matter anymore. The divine exists only if humans haven’t fallen out of grace. Divinity was born to separate God’s secretaries from God’s busboys. After we have crushed God’s ego by eating the apple, he says, “Fuck this. I am going to let my son take care of everything.” Desire just wanders and wanders. Enters one place then moves on to the next victim. Faith is birthed from Hope and Hope, according to Livermore (Jesse Livermore was the greatest speculator/investor of all time), Hope is Greed. So, what happens to one’s faith in the divine when they are broken by love? It doesn’t die, it gets converted into greed. And greed leads to bankruptcy of emotions, of finance, of opportunities, and invites desperation.

And then one stops eating donuts with holes.

Paperback

Epub

About Nora Wright

Winner of Editor's Pick Awards at Textnovel

Tantra Bensko: Hello readers of Everything Experimental Writing. Some of you coming to this article will already be familiar with Nora. For example, her first version of her Light Novel, My Favourite Sin, was at the top of its section's charts at the website Textnovel.com. She took it down to revise and started all over, and it's still doing well. It won the Editor's Pick award, certainly deservedly. It's only one one of her narratives that have a substantial following there, where she is a star for good reason. It's my favorite of her work, and also one of my favorite books of all time. I cried, stared at the screen with my mouth open, gasped, said expletives, repeated phrases of it out loud, laughed out loud, talked to myself about it, exclaiming its wonders, shook my head in amazement. My thoughts returned to it day after day, haunted by its excellence. I finally started corresponding with Nora, wanting to know more about her and help more people find her work, and obtain an appreciation for the Light Novel and other aspects of the world she's involved with. People who have only read her work at Textnovel may enjoy getting to know her better here.

Other readers might be surprised by an interview with someone not appearing in magazines. Nora doesn't particularly read literary magazines, which is no doubt true of many Textnovel members. She reads Manga extensively, however, and like many members there, she uses some of those conventions in her presentations, such as the art, and the convoluted, intensely dramatic plots involving young, active people. She of course also reads the material on Textnovel. It's a whole self-contained world, though some authors there have had their work published outside of that site.

Some writers, such as Nora, also put their work up at Wattpad, and spend time reading the other works there. Such communities tend to be more directly interactive than many magazines, though those sometimes have forums, Facebook pages, representation at AWP, etc. and the individual authors tend to network heavily.

In fact, while people coming from the Literary magazine direction might be surprised to see all this work given away for free without the gatekeeper's seal of approval, consider this: in a magazine, the slush readers, and team of editors, or sometimes, the sole editor alone, makes the decision to publish a piece in a journal or anthology. In Textnovel, popularity is shown by page views, Editor's Picks, votes, etc. so it's like having a lot of editors give the seal of approval if a story gains attention.

We must take into account, when using that system to attempt to sanction a story, that there are a majority of readers and writers who are very young, and who like stories about young romance. The paranormal/supernatural genre is also popular, though there is a wide variety of material on the site, and all ages and audiences. Still, the very highest ranking ones find their audience with the majority of the young readers, are the site's version of commercial fiction, and some even use something akin to advertisements within them. Quiet, philosophical literary fiction by an elderly scholar would have more of a challenge in gaining such high ranking there, whereas it has no handicap within most literary magazines. But such a writer might find great inspiration in the new forms such as Cell Phone Novel (CPN) and Light Novel, the direct interaction, a new challenge to write to appeal in a sink or swim way with real-life readers for entertainment.

This is not a perfect system for an outsider to navigate looking for quality alone, as many factors besides that can go into popularity there, and because we don't know who the editors are and their unique credentials and tastes. However, taking some time looking through the site, you'll see you can search by genre, to help narrow it down to your taste. Also it has a handy way of showing you the first bit of the description about each newly added, updated, award winning piece as well as the ones people pay to have brought to the editor's and reader's attention without the need for much searching. If you like one writer, you can see who else she likes, and though most of the narratives on the site would never make sense in a Literary magazine or Literary publisher, there is a Literary section, and some, including some of the genre pieces, could well appear in respected publications.

Author Kyle Muntz says: "It's still rare, but the anime industry produces convoluted, unconventional work a lot more regularly than any visual media over here, which is especially impressive considering how small their budgets can be."

In the Japanese tradition this site arises from, this is the way to get published, especially as it is the first English language website and is the largest source of CPN. In 2007, half of the best selling novels in Japan began as CPN, generally ended up with movies and games. Now 3/4ths of teens in Japan read CPN. TAKATSU has been instrumental in bringing that to North America. Light Novels are also very popular there. Both of these have conventions I'd like to hear Nora describe. I'd like to hear her talk about all sorts of things, so I asked her to get it started with some background about herself.

Nora Wright: I mainly write on Textnovel.Com. Two of my works got Editor Choice Award on Textnovel.Com.

Link: http://www.textnovel.com/story/My-Favourite-Sin/14485/

http://www.textnovel.com/story/Koi-No-Yokan/15093/

Actually, I got the idea of My Favourite Sin because of my online activities. I spend a lot of time online and have met some really great people. I took a bit of the story from real life and a bit of imagination. The start of the story was based on an online relationship I had, but later, I went with the Flow. Writing about a girl with secrets was not tough. We all have secrets. I was anything like my character. But, when I wrote My Favourite Sin, I didn't really plan the story.

I write without thinking. I become my character. Although, my character and I might not have any connection. When I write stories, I don't think. I role play. I become the characters and my mind thinks like them. After that, I switched to my writer self. I create situations and imagine what my character will do in those situations. Will they break or will they fight? I also don't believe in black and white world. That's why, my characters have 'shades of grey' personalities.

I just write. I don't think about my readers. I think, writers are reader themselves. Writing is a way to pleasure themselves. To satisfy themselves. It's like day dreaming and at the same time, having no control what's going to happen in that dream. So, most of the time, I have no idea how the story will end. Sometimes, I surprise myself.

Light Novel or LN is Japanese style novel that are typically not more than 40,000–50,000 words long. These novels are usually directed toward young adults (high schoolers or middle schoolers). On www.Baka-Tsuki.Org, you can find many translated Light Novels.

Tantra: Maybe you could tell people about the conventions of writing a Light Novel as it relates to Manga and Anime. TAKATSU says this on the subject: "Essentially Light Novels are like young adult novella in a Japanese context with Japanese entertainment influences and mythos, that's the extent I know. Perhaps things like what kind of themes are common in Light Novels? A large amount of them are fantasy or sci-fi I believe, if I'm not mistaken, while manga can include more slice of life, romance and so on. How would Light novels compared to magical-realistic (I'm abusing the term) literary fiction? Japanese entertainment and literature often tends to blend and blur the lines. A lot of manga, anime, light novel concepts is hard to categorize into a strict Western genre, like traditional LOTR/Tolkien structured fantasy or space-grown science-fiction. Many feature young characters, who may lead ordinary realistic lives, etc. We would both be interested in hearing your perspective.

Nora: illustrations. The difference between Novellas and Light novels. Anime/Manga illustrations are used in Light novel. Also, Light novels are more straight forward and dialogue oriented. Light novels are alter ego of Manga, I think. In Manga, we see more pictures and less words. In light novels, More words and less pictures. Light Novels are like Manga, but in novel form.

Themes that are common in light novels: So far, I have read light novels on Baka-Tsuki.Org. I would say mystery, adventure, paranormal, fantasy and science-fictions are more common. There is romance too. Most light novels I read are either shounen or narrator point of view (not personal narrative). Because light novels are like Manga, so I see harem in there a lot too. I have read quite a slice of life genre light novels. They are not as much as the fantasy or science fictions, but it must be because there are not that are translated in English. In slice of life genre, my favorite is Toradora and Papa no iu koto o kikinasai. In fiction, I like Utsuro no Hako to Zero no Maria and Tokyo Ravens. I wish to write like them someday.

As compared to Novella, literature and other western genre: Light novels are more straightforward like Manga and also, it's serialized in small novels form. When I read Light Novels, they had a light feeling to them. It's directed toward High Schoolers or late teens. Fan service is also included in light novels. I think, the word limit, illustration, straightforward or manga like writing is the main difference. Like, Manga it is written in the form of words and few anime illustrations are added. A light novel without illustrations isn't a complete light novel.

Tantra: Thank you very much, very clear and helpful analysis. Now, let's look more directly at your narrative. Here is an intriguing quote from the Light Novel that expresses the search for identity, the effect of the protagonist's partial amnesia, and the mystery of how that relates to the people closest to her. Would you like to start with this jumping point to address this section and anything else about the plot, themes, and characters that might draw readers toward reading My Favourite Sin on Textnovel, or bringing new understanding of it to its fans? What mysteries within it can you discuss here without giving too much away?

""Are you enjoying?" We are on the Ferris Wheel. He is sitting very close to me. I notice it now. I have followed absent-mindedly on the Ferris Wheel. Noah is still holding my hand.

"I want to tell you something." Noah says in a serious tone. "The reasons I did those things to you."

My ears perk up. I turn my face to him and our heads bump. His honey eyes are so sad. I have only seen those expressions on somebody else. I jog my memory. I can't remember that person. Its been too long. I can't even tell how long.

"Because I love you." Noah's voice is so soft that my heartbeats slow down.

I push that person memory in my head. I don't want to remember him.

Because that person is gone and I am not good enough for him anymore. I am not the Mira I was once. I have killed people. I have lied. I have turned into everything that person would hate. I have broken my vow with that person.

But just like now, that person confessed loving me on a Ferris Wheel when my parents were alive. I can't remember that person anymore. I repressed those memories. This moment with Noah is making me dig it again.

That's why it feels like Deja Vu.

"I am sorry that I have hurt you." Noah cups my face with his hands. "But I have loved you for a long time. I did everything to get you back. If I haven't done it, you would never have come out of your shell."

He is right. I have locked myself in the DWO world and lived a mirage until now. In my both worlds, everyone thought that I was perfect until I met White Whisper. My world was torn open by him when I went out with that middle aged man to save my DWO life.

When did I become like this? I can't tell. For last five years, I did everything to create a world where nobody could raise their fingers on me. Not even my dead family."

Nora: Mira or Miranda Roy is a hollow person who is trying to make up for the holes in her life by being a perfect girl who mastered everything. To her, winning is everything, since it will give her temporary satisfaction. She is baffled by her questions from her own mind and that's also the reason that she wants to be the perfect girl, to stop her own heart to ask her questions that are linked to her dark past. She is also a violent R+ game player.

Her life was peaceful until she gets a message from another game player named White Whisper who knows the secrets of her dark past that she is trying very hard not to remember. White Whisper is manipulative and cunning. He knows everything and he controls her life. Soon, Mira finds her perfect life mirage breaking. Her wounds are being cut open and she can't do anything about it.

Then, there is Noah- Her classmate. She suspects him of being White Whisper. When he confessed in the scene, she believed him. You can see that she almost forgives him when she realizes that he loves her. Her simple need is love -- not particularly romance. She realizes that her life is a mirage that she has built in the last five years. It's not perfect. Underneath that mirage, she is standing there alone.

An article I find helpful about the history and circumstances behind the appearance of the visuals: Why Do Manga and Anime Characters Look the Way They Do

Our recommended Anime Death Note.

Other readers might be surprised by an interview with someone not appearing in magazines. Nora doesn't particularly read literary magazines, which is no doubt true of many Textnovel members. She reads Manga extensively, however, and like many members there, she uses some of those conventions in her presentations, such as the art, and the convoluted, intensely dramatic plots involving young, active people. She of course also reads the material on Textnovel. It's a whole self-contained world, though some authors there have had their work published outside of that site.

Some writers, such as Nora, also put their work up at Wattpad, and spend time reading the other works there. Such communities tend to be more directly interactive than many magazines, though those sometimes have forums, Facebook pages, representation at AWP, etc. and the individual authors tend to network heavily.

In fact, while people coming from the Literary magazine direction might be surprised to see all this work given away for free without the gatekeeper's seal of approval, consider this: in a magazine, the slush readers, and team of editors, or sometimes, the sole editor alone, makes the decision to publish a piece in a journal or anthology. In Textnovel, popularity is shown by page views, Editor's Picks, votes, etc. so it's like having a lot of editors give the seal of approval if a story gains attention.

We must take into account, when using that system to attempt to sanction a story, that there are a majority of readers and writers who are very young, and who like stories about young romance. The paranormal/supernatural genre is also popular, though there is a wide variety of material on the site, and all ages and audiences. Still, the very highest ranking ones find their audience with the majority of the young readers, are the site's version of commercial fiction, and some even use something akin to advertisements within them. Quiet, philosophical literary fiction by an elderly scholar would have more of a challenge in gaining such high ranking there, whereas it has no handicap within most literary magazines. But such a writer might find great inspiration in the new forms such as Cell Phone Novel (CPN) and Light Novel, the direct interaction, a new challenge to write to appeal in a sink or swim way with real-life readers for entertainment.